When Rep. Joe Neguse delivered his closing remarks in February at the impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump, he expressed concern about the direction of a nation that weeks earlier witnessed a homegrown attack in its capital.

“I fear, like many of you do, that the violence we saw on that terrible day may be just the beginning,” said Neguse, D-Colo., who as an impeachment manager had a nationally televised role in prosecuting Trump on a charge that he incited the mob that stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6.

Neguse ended optimistically, offering a favorite quote from Martin Luther King Jr.: “I’ve decided to stick with love. Hate is too great a burden to bear.”

The Senate acquitted Trump. A day later, Valentine’s Day, the propulsive threatening discourse that Neguse worried was taking root in American democracy landed on his doorstep.

A suspicious letter mailed to the congressman’s home was opened to reveal a picture of Neguse clipped from The New York Times. An unknown substance, suspected to be feces, marked an “X” over the photo, according to records kept by the police department in Lafayette, Colorado, and obtained by NBC News.

The disturbing incident, which has not been previously reported, was referred to the Capitol Police for investigation and is among the more than 9,000 threats the agency is expected to log this year. It’s also representative of the escalating security risks confronting public officials from the federal and state levels down to local school boards.

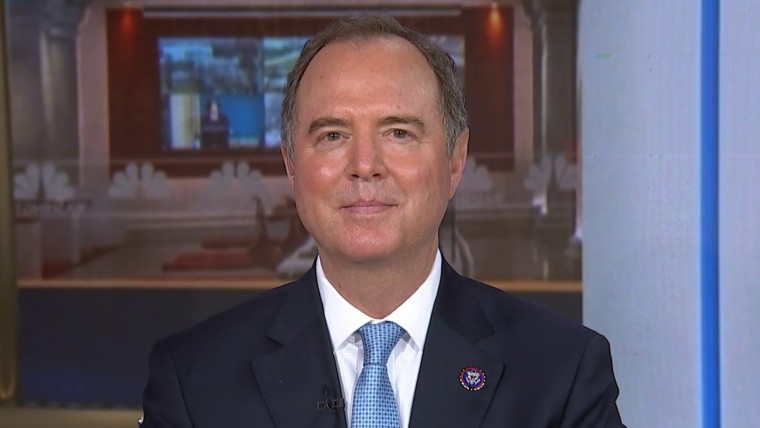

Rep. Schiff: Jan 6th Committee will hold witnesses refusing to comply with investigation ‘in criminal contempt’

OCT. 13, 202107:43“I had one person call and say, ‘This is the gun I’m going to use. I’m going to put three bullets in the back of his head,’” Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., said last month on MSNBC. “You find yourself feeling uncomfortable sitting next to an open window in your home. And that’s not something I ever thought I would have to think in this country.”

Quantifying exactly how dangerous things have become is a challenge, but even elections officials — a less prominent rung of public service that is nonetheless central to democracy — are reporting threats.

And officials with the Capitol Police, the agency responsible for protecting members of Congress, have said they expect the number of threats against members to surpass the 8,600 handled in 2020 and continue a significant surge during the Trump era. In 2017, the first year of Trump’s one term, only 3,900 threats were reported. (The department is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act, making specifics scarce.)

While Trump has fomented much of this hostility among fellow Republicans, anger on the left has risen, too. Republicans practicing for the annual congressional baseball game were targeted by a shooter known for anti-GOP sentiments in 2017. Republican senators during Trump's term faced threats for supporting his conservative Supreme Court nominees. Progressive activists during the early months of the Biden administration have pushed boundaries in their encounters with moderate Democrats, such as Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona.

NBC News, in requests to nearly 70 state and local law enforcement agencies, sought records detailing any threats over the last year to 37 public officials. The list included congressional Republicans who voted to impeach or convict Trump; Democrats who, like Neguse, served as impeachment managers; and high-profile governors and secretaries of state. Most agencies reported having no relevant documents or cited legal exemptions that prevent the disclosure of a public official’s security concerns.

Covid-19 and the 2020 presidential election have fueled much of the rage. The FBI last year thwarted an alleged plot by extremists to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, because of restrictions she imposed during the pandemic. The Jan. 6 riot in the Capitol was an attempt by Trump supporters to prevent Congress from certifying Joe Biden’s Electoral College victory.

“People are mad and angry, and I understand that,” Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican who faced death threats while resisting Trump’s pressure to overturn Biden’s win in his state, said in an interview. “But they feel that they can say whatever they want to say and actually make threats against your life, because they're mad at the election results. What's distressing is … the reason that they believe this is that they've been lied to.”

More recently, the sinister tone of political dialogue has expanded to smaller partisan grievances and debates over policy, with Trump and Republicans egging on the vitriol.

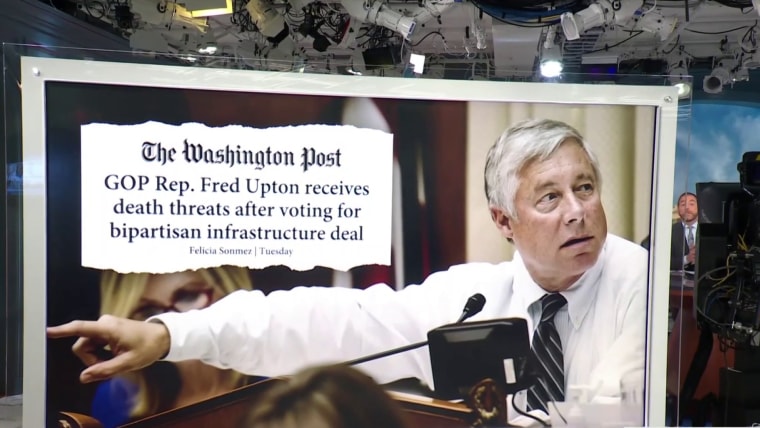

Rep. Fred Upton, R-Mich., went public with death threats he received this month after Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga., called him and 12 other GOP colleagues who voted for a Trump-opposed infrastructure bill “Republican traitors” and shared their office telephone numbers on Twitter. Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Ariz., was censured last week by the Democratic-led House after posting an anime video that depicted him attacking Biden and killing Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y.

GOP leaders rarely condemn such behavior. But there have been broader and more tangible consequences.

Rep. Anthony Gonzalez, R-Ohio, is not seeking re-election next year, citing in part the “chaotic political environment” and the threats he received after voting to impeach Trump in January. Others are limiting how much they interact with the public.

The Congressional Management Foundation, a nonprofit group that helps members run their offices and engage constituents, has advised that in-person forums are a security risk. Bradford Fitch, the nonprofit’s president and CEO, said he also urges staffers to send unknown calls straight to voicemail, to spare young aides the verbal abuse.

“I will give you an anecdote that was very chilling that happened to me recently when I was doing a training for some new interns coming to Capitol Hill,” Fitch said. “Normally, the question you get is, ‘Hey, where are the receptions where the free food is at?’ Instead, the question I got was, ‘I just did my training for answering the phones, and my chief of staff wants me in cases where we get death threats to try to get the person calling to give us their name. You have any advice on how I do that?’”

Through NBC News’ public records requests, several previously unreported incidents came to light.

Rep. Tom Rice, a South Carolina Republican who voted to impeach Trump in January, received a menacing voicemail a few weeks later from a constituent in Myrtle Beach, according to a report from the Horry County Sheriff’s Office. The caller wanted Rice to “come over to his house for coffee so that he could beat the living hell out of him,” the report stated. Deputies visited the suspect, who admitted to making the call but said he had no plans to act on the threat. Rice declined to pursue charges.

Rep. Ted Lieu, D-Calif., was threatened with a “citizen’s arrest” several days after the Jan. 6 riot, according to a report from the Torrance Police Department. Although the report said there was no “articulable threat,” officials noted Lieu “has been vocal and in the forefront of national media supporting the removal or impeachment of President Trump.”

Torrance police have received at least four other patrol requests this year for Lieu, who was a House impeachment manager, including an April call from the Capitol Police that mentioned “threats of bodily harm” to the congressman.

Other members, through their staff or the Capitol Police, have made similar requests to local police and sheriff’s departments this year, citing threats or safety concerns.

Sen. Susan Collins, a Maine Republican who voted to convict Trump at the February impeachment trial, had at least 77 “property checks” at her home and local office between Jan. 6 and Sept. 1, according to Bangor police records. There also were at least two reports of suspicious behavior at her home: a drone flying overhead on Jan. 15 and a man leaning against a nearby fence March 19. Neither turned out to be a threat. Collins, a moderate with a high-profile swing vote, has been dealing with threats and harassment for years, including for her 2018 vote to confirm Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, a Trump nominee.

Property checks “are usually in response to a vague or potential threat” relayed by Capitol Police, Bangor police Sgt. Wade Betters said. “Generally an extra precaution type thing.”

Ohio’s Gonzalez and Rep. John Katko, R-N.Y., also reported threats after voting to impeach Trump, according to records obtained from their local police departments. Patrols were increased near their homes.

The records don’t always capture the full size of what a public official is facing. A November 2020 security check at Raffensperger’s suburban Atlanta home, for example, alluded only to his family “receiving multiple threats.”

Raffensperger has offered more details publicly, in interviews and in “Integrity Counts,” the autobiography he published this month. The attacks intensified as Raffensperger refused to support Trump’s false claims that he had won Georgia. His wife, Tricia Raffensperger, received “sexualized” threats, Raffensperger wrote in his book. Someone broke into their widowed daughter-in-law’s home. The family briefly went into hiding.

“We could have stayed,” Raffensperger said of the decision to leave their home temporarily. “But what happens if the situation gets out of control? What if the situation would have developed? So that was just something that was really about, not just us, but also for our grandchildren and our children.”

Raffensperger is seeking re-election next year and faces a Trump-endorsed primary challenge from Rep. Jody Hice. The threats have dwindled, he said, but he received “some nastygrams” after his book was released. “They were just dog-cussing me,” he said, “as we like to say in the South.”

But in times of inflamed tensions and heightened alert, it’s become easy to assume the worst.

At home in Colorado with his wife and toddler, on the day he received the defaced news clipping, Neguse treated flowers that had unexpectedly arrived for him with the same suspicion.

Capitol Police later determined the flowers were no threat — just a friendly gift from a colleague in Congress.

Get the Morning Rundown

Get a head start on the morning's top stories.