|

Msg ID:

2703287 |

Opinion | It’s Time to Dismantle America’s Residential Caste System +2/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/13/2021 10:30:18 AM

|

I can't wait for some knee jerk extreme right wing reactionary tio respond with 'property rights'.

I remember desegregation and 'they don't want to mix with us' and 'separate but equal schools'.

At least make up some new shyte, Mr Charlie.

In his repeated calls for “law and order” and his characterizations of places such as Baltimore as rat-infested havens for criminals, Donald Trump did more than any politician in recent memory to perpetuate myths about inner cities, pitting urban dwellers against suburbanites. “Our inner cities are a disaster. You get shot walking to the store. They have no education. They have no jobs,” Trump declared in 2016.

Four years later, in announcing that the federal government would no longer require localities to analyze their housing patterns and redress segregation, Trump tweeted: “I am happy to inform all of the people living their Suburban Lifestyle Dream that you will no longer be bothered or financially hurt by having low income housing built in your neighborhood.”

While his style was more blatant, Trump was only the latest among presidents and presidential aspirants across five decades to weaponize racialized “ghetto” stereotypes, beginning with the dog whistling George Wallace and Richard Nixon used in the wake of urban uprisings in the 1960s. The perennial message: High-opportunity suburban living is earned, and 'hood living is the deserved result of individual behavior.

The physical lines that divide America into racialized spaces of high and low opportunity are real. But what Trump and many others have long ignored is the role that federal and state actors have played for decades in creating and perpetuating those divides, through past and present forms of racial segregation, and through the distribution of resources away from those who most need public goods and toward people and communities with more than enough.

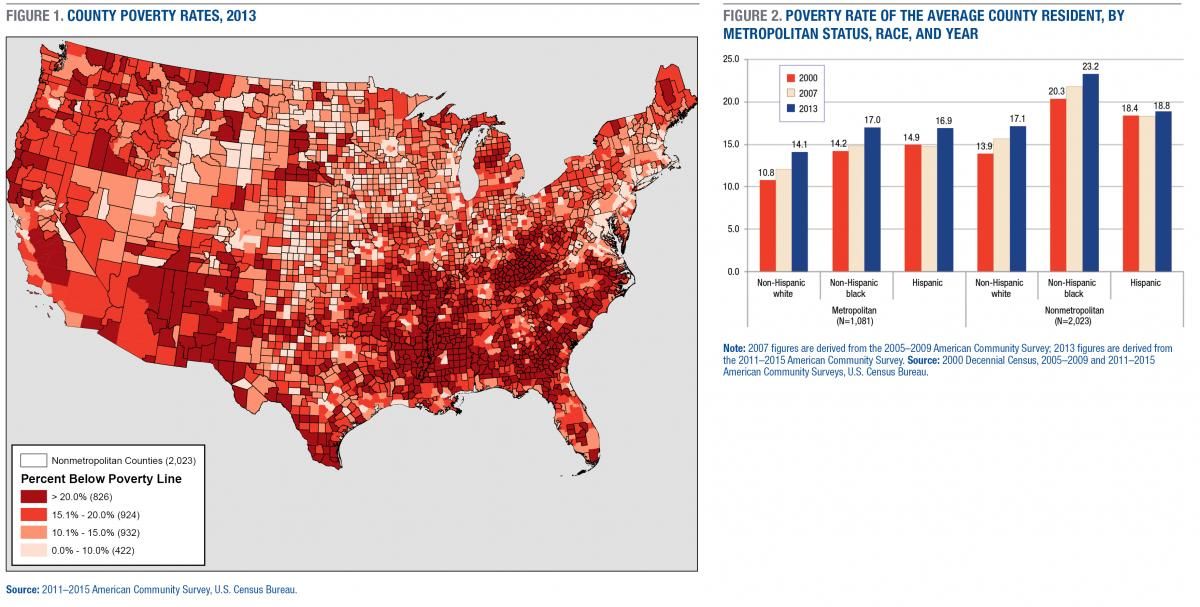

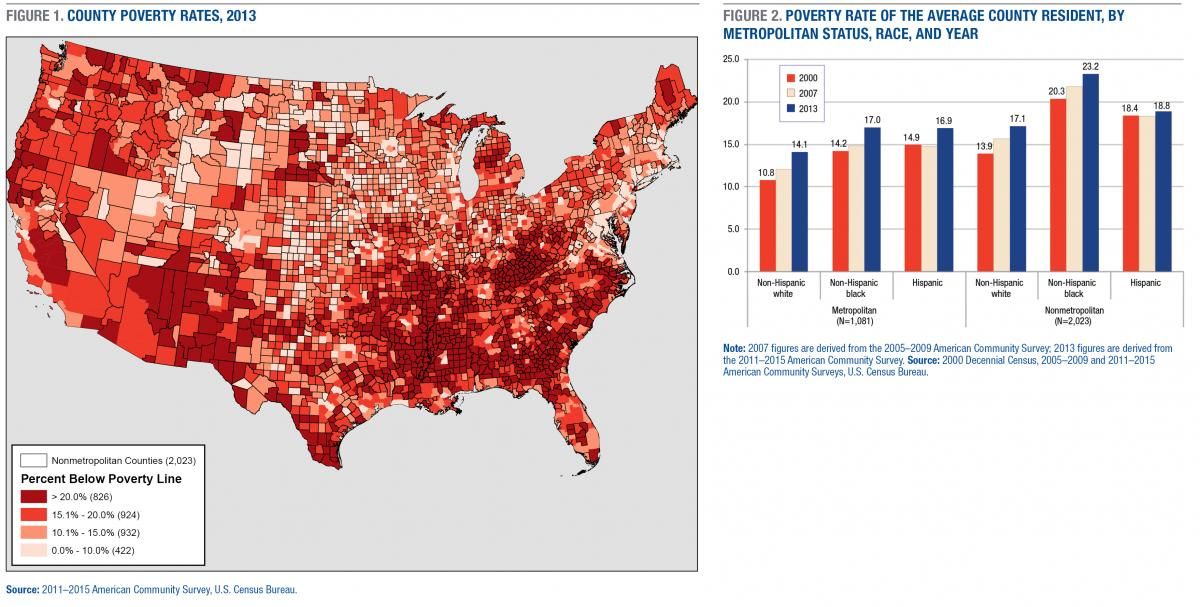

These divides can literally be mapped, revealing the geography of racial inequality in America. While we don’t always think about it in this way, geography is key to understanding where and why inequality persists — and key to redressing it.

Maps can illuminate both the origins and the persistence of neighborhood inequality. Rates of poverty in America are highest in segregated communities of color and lowest in segregated white neighborhoods. Only about 30 percent of Black and Latino families reside in middle-class neighborhoods where less than half the people are poor. But more than 60 percent of white and Asian families live in environs where most of their neighbors are not poor.

Neighborhoods with high rates of poverty, limited employment, underperforming schools, distressed housing and violent crime depress life outcomes. Meanwhile, residents of exclusionary affluent spaces rise on the benefits of concentrated advantages, from excellent schools and infrastructure to job-rich social networks to easily accessible healthy food. Less understood is the fact that the government-created Black 'hood facilitates poverty-free affluent white space, by concentrating poverty elsewhere.

Majority-Black neighborhoods set apart from bastions of white affluence have a long and enduring history. They were constructed in the first half of the 20th century to contain millions of Great Migrants who moved North and West to escape Jim Crow. Black Americans in the first great wave of migration to Chicago, for instance, were largely confined to an 8-square-mile area referred to as the Black Belt. Later generations called it the South Side, future home to Michelle Obama. Wherever migrants landed in large numbers they were intentionally, sometimes violently, contained. Their neighborhoods were redlined, cut off from public and private investment and preyed on by speculators for profit.

Anti-Black habits of disinvestment and plunder continue to this day. Government at all levels overinvests in affluent white space and disinvests in Black neighborhoods, with the exception of excessive spending on policing and incarceration. Many current public policies and processes encourage rather than discourage racial segregation. And competition between communities of abundance and communities of need sets up a budgetary politics in which affluent spaces and people usually win out. The end result is more residential sorting: A recent comprehensive analysis by the Othering and Belonging Institute found that 81 percent of metropolitan regions with a population above 200,000 were more segregated in 2019 than they were in 1990.

These mean realities should be called what they are — a system of residential caste that harms those who cannot buy their way into bastions of affluence, which is most Americans. Residential caste also contributes to the broken politics from which we all suffer: Racial segregation makes it easier for cynics to draw political boundaries that create ideological extremes, and for dog-whistling politicians to stoke fear and division.

At the same time, acknowledging and understanding the central role of geography in creating and maintaining American caste opens up new avenues for transformation, offering an inherently organized, spatial mechanism for identifying communities that most deserve new investment from the government and private sector, and those that need less — a necessary process of abolition and repair.

America’s system of residential caste is ingenious in its ability to hide the truth of how and why we subordinate some and lift up others. But I have identified three primary processes through which the 'hood and affluent white space persist: boundary maintenance, opportunity hoarding and stereotype-driven surveillance.

Boundary maintenance consists of intentional state action to create and maintain a racialized physical order. Over a century, it has included racially restrictive covenants, exclusionary zoning that limits where multi-family buildings can be built, urban “renewal” projects that removed Black residents, intentionally segregated public housing, an interstate highway program laid to create racial barriers, endemic redlining, as well as disinvestment in basic services such as schools and sewage in Black neighborhoods.

While not all of these practices continue now, the federal government still invests in segregation. To date, George Romney, Sen. Mitt Romney’s father, is the only HUD secretary to have pressured and penalized communities for exclusionary zoning laws and for refusing to build affordable, nonsegregated housing. For his egalitarian deeds, President Nixon forced Romney to resign. Over ensuing decades, both HUD and local governments regularly violated the Fair Housing Act of 1968 requirement that communities “affirmatively further” fair housing. For decades, HUD has distributed about $5.5 billion annually in grants for community development, parceled among more than 1,000 local jurisdictions nationwide, with no meaningful accountability for promoting integration.

Top: President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Fair Housing Act in 1968. Bottom: Housing and Urban Development Secretary George Romney, left, President Richard Nixon, center, and Washington Mayor Walter Washington look at a proposal for a new park in a riot-wrecked, poor, predominantly Black section of the nation's capital. | AP Photos

The federal government also funnels about $10 billion annually through the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program for affordable housing construction. But it mostly results in construction in poor communities that already have more than their fair share of affordable housing. Nationally, only about 17 percent of LIHTC projects are built in high-opportunity neighborhoods with high-performing schools, low crime and easy access to jobs. That keeps those Americans who need affordable housing concentrated in the same low-opportunity areas.

Another program, HUD’s Housing Choice Vouchers, provides rental assistance to low-income tenants, but the program does not disrupt entrenched racial and economic segregation. Most Black and brown voucher holders land in low-opportunity areas, where more than 20 percent of residents are poor, while white voucher holders tend to find rentals in lower-poverty areas.

Thankfully, the Biden administration recently restored the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule that Trump tweeted about suspending. A few conservatives or libertarians criticize the AFFH rule for not pressuring localities to deregulate exclusionary zoning codes that insulate single-family housing from more dense residences such as apartments. But vocal opposition to inclusive housing can be found in both Republican and Democratic territory. In blue California, the state legislature failed to pass a critical bill that would have suspended local single-family zoning to help solve the state’s massive affordable housing crisis, though California recently passed legislation to force localities to open single-family 'hoods to duplexes.

While the vast majority of white Americans reject segregation in public opinion surveys, in practice their willingness to enter or remain in a neighborhood declines sharply as the percentage of Black neighbors increases, studies have found. The average white person lives in a neighborhood that is 76 percent white. Although most Black Americans no longer live in high-poverty Black neighborhoods, those 'hoods persist, as does the architecture of segregation. About half of all Black metropolitan residents live in highly segregated neighborhoods.

In a comprehensive study of neighborhood change between 1990 and 2010 in America’s 50 largest cities, geographer Elizabeth Delmelle found that neighborhoods of concentrated Black poverty remained the most persistent type, followed by those of concentrated white and Asian affluence. The boundaries of these neighborhoods at polar extremes hardened, while more moderate-income, multiethnic neighborhoods became more fragmented, showing more possibilities for racial and economic mixture.

Still, intentional segregation of Black people in the 20th century shaped development and living patterns for everyone and put in place an infrastructure for promoting and maintaining segregation that lives on. Racial steering by realtors who nudge homebuyers into segregated spaces, discrimination in mortgage lending, exclusionary zoning, a government-subsidized affordable housing industrial complex that concentrates poverty, local school boundaries that encourage segregation, plus continued resistance to integration by many but not all white Americans — all are forms of racial boundary maintenance today.

The segregation of affluence facilitates opportunity hoarding, whereby wealthy neighborhoods enjoy the best public services, environmental quality and private, public and natural amenities, while other communities are left with fewer, poorer-quality resources. Worse, suburban-favored quarters are subsidized by the people they exclude: Through income and other taxes, people of all racial and class backgrounds who live elsewhere help pay for the roads, sewers and other infrastructure that make these low-poverty, resource-rich places possible.

v class="container container--story story-layout--fixed-fluid">

This pattern of overinvestment in exclusionary, predominantly white space and disinvestment or neglect elsewhere is replicated within cities across the country. In her book Segregation by Design, Jessica Trounstine amasses empirical evidence to support her theory that segregation creates a city politics that reproduces inequality — a racial hierarchy of favored and disfavored residents. After local governments deployed land use, slum clearance and other policies to tightly compact Black Americans beginning in the early 20th century, those residents also were denied adequate sewers, roads, garbage collection and public health services. Segregation institutionalized the preferences of white property owners, protecting their property values and giving them exclusive access to high-quality public amenities — a nefarious pattern that continues. Today, business elites bend local government to their will, ensuring that the luxury residential and commercial development they want gets built, regardless of competing community and housing needs.

In the first two decades of the new millennium, public and private investment rained down on favored parts of central cities. Black Americans, in contrast, continued to be denied. For example, a 2019 Urban Institute study found that majority-white neighborhoods in Chicago received about three times more public and private investment than majority-Black neighborhoods.

Neighborhoods on an upward trajectory, such as those in what’s known as the “White L” in Baltimore, were shaped in part by investors’ avoidance of Black and Latino people. In post-industrial cities that “revitalized” since 2000, areas targeted for development — usually downtown, near a university, a hospital or another key institution — became whiter. Yet in these same cities and era, Black neighborhoods, even some middle-class ones, often became poorer.

The city of Chicago demonstrates these stark divides all too well. Chicago’s largest and most populous neighborhood, Austin, is overwhelmingly Black. About 40 percent of its residents earn less than $25,000 annually. It was savaged by foreclosures after the financial crisis of the late 2000s, yet excluded from many of the city’s key neighborhood development programs.

Top: Police arrest protesters in Chicago in 2013. Bottom left: Rahm Emanuel, then-mayor of Chicago, in 2013. Bottom right: An activist speaks at a Chicago Board of Education meeting in 2013. | AP Photos

I call the Black people trapped in high-poverty neighborhoods “descendants,” in recognition of an unbroken continuum from slavery. For descendants on the South and West sides of Chicago, watching booming downtown development while the city shuttered school after school in their neighborhoods added to the insult. Chicago had closed 70 public schools over eight years by 2012. Then, in 2013, Mayor Rahm Emanuel closed 50 additional public elementary schools — the largest one-time mass school closure in the country. The Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois at Chicago found that schools with large numbers of Black students had a higher probability of closure than other schools with comparable test scores, locations and utilization rates.

v class="container container--story story-layout--fixed-fluid">

As school infrastructure evaporated in Black 'hoods, the city invested in new options elsewhere. An investigative report by a local public radio station in 2016 revealed that new school building expansions after the 2013 closures were “overwhelmingly granted” to specialized schools that serve relatively low percentages of low-income and Black students.

Private actors also favor whiteness and disfavor Blackness. The Center for Investigative Reporting released a study in 2018 that analyzed 31 million records revealed by the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act and found a disturbing pattern of denials by banks of Black and Latino applicants for traditional mortgages where white applicants with similar qualifications would be accepted. This modern-day redlining persisted in 61 metro areas, from Atlanta to Detroit, Philadelphia to San Antonio. The greater the number of Black or Latino people in a neighborhood, the more likely a loan application would be denied.

Borrowers from these neighborhoods are also more likely to be preyed on with subprime credit products. Large financial firms, backed by private equity investors, swarmed like vultures to pick through the carrion of the foreclosure crisis. They could purchase a foreclosed home at auction, say for $5,000, and sell it immediately with no repairs through a land contract for $30,000. The land contract is designed to produce failure by the buyer, who believes she is acquiring a home but in fact accumulates no equity unless and until the final installment is made. According to the National Consumer Law Center, Black and Latino people in marginal neighborhoods are disproportionately targeted for this plunder. Their dollars, earned through work we have come to acknowledge as “essential,” should gain them equity, but instead are transferred to financial titans.

Cities, too, engage in financial predation. A recent study by the Center for Municipal Finance found that cities are taxing owners of low-valued properties at higher rates than they should relative to actual land values, while taxing owners of high-valued properties at lower rates than they should.

Geography ultimately reifies power and opportunity for the few who live in rich neighborhoods and contributes to powerlessness and permanence of poverty for descendants.

Government does overinvest in Black neighborhoods in one area: punitive practices such as policing, law enforcement and incarceration. In many cities, Black people are disproportionately arrested for a range of offenses, including much non-violent behavior such as driving without a permit that under-policed whites can engage in with impunity.

What explains separate and unequal policing? George Floyd’s slow execution last year ushered a new national focus on racist policing. Less clear in that radical moment was the role of segregation. Floyd died in the racially mixed Powderhorn neighborhood of Minneapolis, due south of very poor Black neighborhoods on the south side and not far from a dividing line to affluent white space. Like every other segregated city, Minneapolis’ stark segregation was constructed with great intention. According to recent geographically mapped data published by the New York Times, since 2015 Minneapolis police used force against Black people at seven times the rate of whites. Police wielded guns, chemical irritants, Tasers, chokeholds, body-pins, fists and other brute force in the very Black 'hoods of the Northwest and the Southside of Minneapolis. The white working-class Northeast quadrant, across the Mississippi River from Black areas, were spared such intense use of force, as was the affluent white Southwest area.

Another function of anti-Black policing is economic plunder. In 2014 alone, New York City received nearly $32 million from fees, fines and surcharges paid to the criminal courts by people facing misdemeanors, summonses or other low-level violations. Researchers estimated that, over two decades, the city’s take from its “zero tolerance” policing exceeded a half billion dollars. They concluded that most of these revenues were “extracted from relatively poor segments of the population, who live in heavily policed neighborhoods.”

v class="container container--story story-layout--fixed-fluid">

Although aggressive policing produces some revenues for local governments while harming Black citizens, it also produces liabilities that harm all taxpayers. A UCLA law professor looked at payouts by large cities to victims of police misconduct over five years and found they totaled nearly three-quarters of a trillion dollars. Perhaps the only beneficiaries of systemic anti-Black policing are owners and shareholders of corporations that profit from mass incarceration. In Chicago, there are 851 city blocks in which taxpayers spend more than $1 million per block to incarcerate residents who live there. Those blocks are concentrated on the West and South sides, in the 'hoods that Chicago built to contain descendants.

Children, too, are swept into the carceral state. As with segregated neighborhoods, segregated schools facilitate an entirely different relationship between police and young citizens. One legal scholar found that a school’s percentage of minority students and of poverty is a strong predictor of the use of strict security measures, even after controlling for actual levels of school crime and disorder. In New York City, 5,200 full-time police officers patrolled public schools as of 2017, while the schools employed only about 3,000 guidance counselors.

Then there are the ways in which the state encourages private surveillance of Black Americans by self-appointed citizen patrols. Barbecuing by a lake in Oakland. Entering one’s own gourmet lemonade business in San Francisco. A registered guest at a hotel in Portland, Oregon, taking a call from his mama in the lobby. A child mowing lawns for candy money in a Cleveland suburb. These and other acts of “living while Black” resulted in calls to the police. This is what living in white space can do to some people. Those used to being dominant, or unused to seeing dark bodies around, become suspicious of Black people doing utterly ordinary things.

As with slavery, as with Jim Crow, law and social practice continue to allow non-Blacks to monitor and police Black bodies. The worst of these social practices is violent vigilantism. Ahmaud Arbery. Trayvon Martin. Emmett Till. Arbery’s killers were charged and prosecuted. But the state of Georgia enabled their vigilante behavior through permissive laws that make it easy to obtain a gun and encourage, rather than discourage, using it. Georgia, like nearly three-quarters of U.S. states, has a “stand your ground” law that eliminates any duty to retreat and entitles gun owners to use force when they “reasonably believe” it is necessary to defend themselves or others.

Other laws quietly enable surveillance of Black folk to protect white space. An estimated 2,000 localities in 48 states have adopted “crime-free housing” or chronic nuisance ordinances that make landlords responsible for the actions or nonactions of their tenants. Such ordinances often are adopted following an influx of racial diversity. They explode the range of activities that can cause an eviction, and, according to law professor Deborah Archer, they are enforced disproportionately against Black tenants.

When a tenant tries to seek protection from the state, calling 911, say, to control a violent partner, in places with chronic nuisance ordinances, she can be evicted if she calls two or three times. Faribault, Minnesota, for example, adopted one of the harshest ordinances in the country. The ordinance prohibits disorderly conduct by tenants or their guests and gives Faribault police the power to order an eviction without an arrest or conviction of any crime.

Descendants cannot win. They are surveilled, overpoliced and under-protected.

Healing a nation that began with, and still suffers from, white supremacy requires abolition of the processes of residential caste and repair in poor Black neighborhoods. The state is obligated to repair what it put in motion and continues to reify.

But understanding and acknowledging the role of geographic lines in structuring racial inequality presents an opportunity — a targeted mechanism for transformation. My theory of repair is that those most traumatized by the processes of residential caste most deserve care, as well as the chance to be agents in their own liberation. That means government can and must prioritize those neighborhoods that are at the center of anti-Black residential caste in America.

To begin, the state should dismantle and reverse current anti-Black processes of residential caste — through investment in Black neighborhoods rather than, rather than redlining and economic predation; inclusion, rather than boundary maintenance; equitable public funding, rather than overinvestment and hoarding for high-opportunity places; humanization and care, rather than surveillance and stereotyping.

I suggest three critical pillars to guide government action. First, we must change the relationship of the state with descendants from punitive to caring. Second, the state should see descendants as potential assets and empower them to be change agents. Finally, government must invest resources and transfer assets to support descendants and respected community institutions in Black neighborhoods.

Among the new processes that might be implemented would be a regular neighborhood analysis that looks critically at all the money being spent by a state across neighborhoods, with a constant evaluation of racial equity. Seattle, Minneapolis and a few other cities formally require a racial equity analysis in budgeting. Baltimore recently amended its city charter — by ballot initiative — to establish a permanent fund to advance racial equity in housing, education and capital expenditures.

Applying a humane lens to descendants frees policymakers to innovate and focus on evidence-based strategies that might be cheaper and certainly more effective than punitive strategies borne of racial dogma. Researchers at the University of Chicago Crime Lab and the University of Pennsylvania found that a program that gave Black teens in high-violence neighborhoods a summer job and an adult mentor reduced arrests for violent crime by 43 percent. A peer-reviewed independent study found that a “peacemaker fellowship” to support young men most vulnerable to violence in Richmond, California, was associated with a 55 percent annual reduction in gun-related deaths. The organization Advance Peace is helping other cities replicate the program. Other approaches, such as a universal basic income pilot program in Stockton, California, have had promising results. And several cities are responding to activists’ demands for collective ownership strategies to combat displacement of communities of color and create sustainable affordable housing.

A woman holds her debit card provided by the city of Stockton, as part of a trial UBI program. | AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli

Perhaps follow the lead of Lawrence, Massachusetts, which made bus lines from its poorest neighborhoods free, as have other cities. Invest in well-resourced, culturally competent education, with reduced class sizes, in high-poverty neighborhood schools. And allow descendants to be first in line in any lottery for accessing great, integrated schools and neighborhoods. Invest in parks and neighborhood centers that offer recreation and human services in poor Black neighborhoods — free services for the freedom and liberation of descendants who have been intentionally trapped in hyper-segregated poverty.

These are just a few of the possibilities. Descendants should be asked what they and their communities need to prosper, and they should play a role in charting community transformation. Ascending multiracial coalitions that believe Black Lives Matter should gather power to mandate inclusionary zoning and fight for school integration, racial equity and the transformation of policing from predatory to humane.

The federal government also has a critical role to play, though national policy reforms admittedly come with significant political challenges. Because federal, redlined, mortgage-insurance programs invested hundreds of billions (in present dollars) in pro-white wealth-building, new investments should be allocated now to Black communities. Historically defunded 'hoods should receive priority for any new federal infrastructure funding. Congress also could atone for the federal legacy of promoting segregation by enacting a law that bans exclusionary zoning. And it could eliminate the $23 billion gap between what America spends on white versus nonwhite school districts by tripling existing funding for the Title I program for high-poverty schools. Whatever proposals for repair win consensus, they could be paid for in part by reallocating funds from punitive strategies that exacerbate racial inequality and repealing recent excessive federal tax breaks for wealthy individuals and corporations.

All levels of government have a moral obligation to stop investing in segregation, to stop doubling down on practices born of a long, sinister, racist past. Paying attention to the role of geographic dividing lines in undermining citizens marks the way forward to a new reconstruction.

|

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703297 |

Internal Google document ties white supremacy to Trump, MAGA, and Ben Shapi +2/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/13/2021 10:52:13 AM

Reply to: 2703287

|

| September 10, 2021 01:35 PM

The revelations are relevant to the national debate over critical race theory , an ideology that encourages people to see themselves and others through the lens of race.

A Google diversity, equity, and inclusion leader created an internal company document that advances the idea in one graphic that Trump, Shapiro, and other conservatives are layers in a "white supremacy pyramid" that culminates in violence and mass murder, according to reporting by Christopher Rufo, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute.

The internal document contains a disclaimer that it was “not legally reviewed” and, therefore, is not to be considered company policy, but it was hosted on Google's internal resources server and made available across the company.

Another graphic in the document claims that “colorblindness,” “[American] exceptionalism,” “Columbus Day,” and “Make America Great Again” are all expressions of “covert white supremacy.”

Google's diversity training team, along with a team of consultants, also created a race education program that includes video conversations with popular liberals who are scholars on race, such as 1619 Project editor Nikole Hannah-Jones and Boston University professor Ibram X. Kendi.

During one of the videos, Hannah-Jones concluded that all white people benefit from the "system of white supremacy," while Kendi claimed that all Americans are "raised to be racist."

When reached for comment by Rufo, Shapiro aggressively pushed back against the Google document's depiction of him and other conservatives.

“All it would take is one Google search to learn just how much white supremacists hate my work or how often I’ve spoken out against their benighted philosophy,” Shapiro said.

“The attempt to link everyone to the right of Hillary Clinton to white supremacism is disgusting, untrue, and malicious,” he added.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Google declined to comment on Rufo's report.

|

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703313 |

Your link missed one big point! +1/-2

|

Author:Old Guy

9/13/2021 11:16:21 AM

Reply to: 2703287

|

Neighborhoods with high rates of poverty, limited employment, underperforming schools, distressed housing and violet crimes have been under the control of the left for years. This article completely avoids the issues of democratic governments that has failed these neighborhoods. |

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703320 |

Fix it. (NT) +2/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/13/2021 11:22:35 AM

Reply to: 2703313

|

|

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703325 |

Fix it. +1/-2

|

Author:Old Guy

9/13/2021 11:39:16 AM

Reply to: 2703320

|

Yes it can be fixed.

QUIT VOTING FOR THE LEFT

useful idiot |

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703347 |

Shall I cite more examples of Republican administered cities with marked +2/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/13/2021 12:32:33 PM

Reply to: 2703325

|

Shall I cite more examples of Republican administered cities with marked racial disparities? Jacksonville FL wasn't enough?

Okay, here's another:

Oklahoma City, OK

The Racial Wealth Gap in Oklahoma Kate Richey, Oklahoma Policy Institute

krichey@okpolicy.org

918 794 3944

www.okpolicy.org www.oklahomaassets.org

|

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703355 |

Mesa AZ Republican administration +2/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/13/2021 12:48:43 PM

Reply to: 2703347

|

Aurea Lazcano, left, dances with friends during her Quinceañera, or 15th birthday party, at her home in Apache Junction.

< /div>

Day One of Series

Mesa has reached a tipping point. What had been a gradual demographic shift has gained momentum over the past decade, fueled by record immigration. One in four Mesa residents now are Hispanic, up from one in 10 in 1990. If the trend continues, the city will be majority Latino within 30 years.

View the slideshow.

"They are our next taxpayers," says Mary Berumen, Mesa’s diversity director. "They are the ones who are going to be supporting us in the future. They are our next leaders."

Mesa Unified School District now has the secondlargest population of Hispanic students in the state. By 2008, the Mesa school district will have a majority of minority students, most of them Hispanic.

Latino-owned businesses in Mesa are multiplying, and the community’s economic clout continues to increase. Employers here find themselves ever more dependent on the young, vibrant Hispanic work force.

Neighborhoods that had been predominantly Anglo are turning over to new Hispanic homeowners, particularly on the city’s west side and downtown.

"It is about mathematics. That change will occur," says Loui Olivas, associate vice president of academic affairs at Arizona State University and a thirdgeneration Arizonan. "Therein lies the challenge and a great opportunity for the East Valley — to accept the changing demographics and embrace what that means to the economic future and well-being of Mesa."

Mesa isn’t alone, but rather a microcosm of a dramatic transformation under way in other parts of the Valley and throughout the state.

By 2035, demographic estimates show Arizona residents will be mostly minority, primarily Latinos. The state already has one of the nation’s fastest-growing populations of English-language learners, according to a new study, with most of them going to a few mostly urban schools, including Mesa’s.

Valleywide, home ownership among Latinos has topped 50 percent. And the number of Latinoowned businesses is expected to grow by 60 percent in the U.S. between 2004 and 2010.

But as the burgeoning Hispanic population carves out a sizeable slice of the American pie in Mesa, there are growing pains. Latino activists and city leaders say fear, racism, resentment and misunderstanding have fostered a culture clash that threatens to unravel the fabric of the community.

The culture that Hispanic immigrants bring with them does not always sit well with their new Anglo neighbors. Many residents — Anglo and Hispanic — complain about once-quiet neighborhoods now filled with loud Latino music, strangers on the streets at night, outdoor cooking and cartpushing vendors.

The neighborhoods in which they’ve lived for decades no longer resemble the place where they raised their kids, and many are moving out.

"It’s not so much accepting change as most people feel like it’s being forced on them," says Ray Villa, the city’s neighborhood outreach director. "People here feel more like their backs are up against the wall, so they have to make a stand."

Villa, a former Chandler police lieutenant, says many Mesa neighborhoods are undergoing a peaceful transition. Indeed, some neighborhoods are being reenergized by new Latino homeowners.

Others, however, are practically at war. Longtime neighbors may not be as inclusive of newcomers they suspect are illegal immigrants.

In Mesa’s core, such as the area near Broadway Road and Robson, some areas are 80 percent to 90 percent rental, Villa says, which means there is little investment in the neighborhood and less incentive to keep properties up to city code. The city doesn’t even have an internal blight code, he says, so there’s no way to keep tabs on the interior conditions of homes.

"When I go into the neighborhoods and I meet with different groups, I see people embracing diversity left and right. I see compassion," Villa says. "But I also see that people are frustrated. They’re frustrated at the federal government for not doing its job. They hear all the stats that are being thrown out there, and they feel like they have to make a stand."

Mesa police receive more than 50 calls a month related to loud music or noise — the highest of the city’s 31 beats — from one of the city’s most culturally diverse neighborhoods, bounded by Broadway, Mesa Drive, Stapley Drive and U.S. 60.

Kim Clarkson, 34, is a west Mesa native who sold her home near Main Street and Stapley Drive to move with her husband and five children into the Groves neighborhood, near Val Vista Drive and Brown Road.

They needed a bigger house, but Clarkson says they also didn’t like the "rundown" look of the Food City and other stores that had taken over nearby strip malls. And she’s uncomfortable with Spanish-language billboards.

"The only words I could understand on the sign were Western Union," she says.

Their decision to move was based on socioeconomic, not racial, factors.

"It’s a matter of whether you want to live near the kind of stores they have at Val Vista and Baseline or the kind of stores they have at Main and Horne," says Clarkson.

Lucy Duarte grew up in Nogales, Mexico, but moved to the U.S. legally when she was 17.

"We’re here, our kids are here, and we’re not going anywhere," Duarte says, shrugging off the tension between Hispanics and Anglos in Mesa. "They need to know more about us, and little by little they will accept us more. They fear us because they don’t know. But between the two cultures we can make each other richer."

At the same time, the demographic shift is creating social, economic and political upheaval, from predatory lending and slumlords to health care and education deficits to the lack of Hispanic representation on city boards, commissions and in elected posts. No Hispanic has been elected to public office in Mesa.

Yet Mesa’s political leaders are doing little to address the social problems surrounding the growing Hispanic population or the fundamental lifestyle changes troubling the city’s Anglo residents. The city doesn’t keep statistics on the growing number of Latino-owned businesses, and the City Council has done little to address the demographic changes, other than a series of debates over a day labor center that ultimately fizzled.

Council members Mike Whalen and Kyle Jones sponsored a town hall forum earlier this year to hear neighborhood concerns, but the discussion devolved into a litany of complaints about loud music and cars parked in yards and paleta salesmen.

But otherwise, there has been little or no action by the city’s elected representatives.

"People have to recognize that Mesa is changing," says Deanna Villanueva-Saucedo, community liaison for the Mesa school district and Mesa Community College. "But no one seems to want to talk about it.

"We avoid it because it brings out all the vehemence that some members of our community have. People are afraid to go down that path . . . and yet those are exactly the kind of conversations we need to be having in our community."

ILLEGALS ARE THE STICKING POINT

Illegal immigration is the political lightning rod that overshadows any public debate on how to cope with problems in the community or in the schools. And it’s true that immigrants are arriving in Arizona and Mesa in record numbers — an estimated 500,000 immigrants are in Arizona illegally. Still, a study by the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute shows that two-thirds of the children of Latino immigrants — and 93 percent under 6 years old — were born in this country, even if one or both of their parents weren’t.

Whether illegal immigrants are a net gain or a huge cost to taxpayers depends on which study you rely upon.

Those who earn low wages, don’t pay taxes, whose children are educated in public schools and who use hospital emergency rooms for their health care are most likely a drain. Those who are approaching middle-class, who pay Social Security taxes — which they will never recoup — and remain relatively healthy are probably paying more into the economy than they take out.

What’s not debatable, however, is that many businesses have grown to rely upon illegal workers.

Still, when state Rep. Russell Pearce, R-Mesa, says "they have turned (Mesa) into a Third World country," as he recently told a reporter for Stateline.org, he speaks to the frustrations of some longtime Mesa residents who see their neighborhoods changing. And he articulates the "us vs. them" dichotomy that Hispanics say further inflames the debate.

"I’m increasingly concerned about the polarization," says Lisha Garcia, Mesa’s neighborhood services administrator. "There isn’t communication between the older, established residents — it doesn’t matter their ethnicity — and the new residents who are coming. And there’s a cultural clash."

Garcia, who was raised in Tucson and spent most of her professional life in San Antonio and Mexico City, says she went through "culture shock" when she and her daughter arrived in Mesa last year.

"I had no idea that this type of cultural isolation was still prevalent in a the Southwest, in a city this size," she says.

During a recent interview, Garcia’s phone rings. It’s her 17-yearold daughter. "He called you a spic?" she says into the phone. "You have every right to be upset. . . . No, honey, you did the right thing." She hangs up the phone and shakes her head. "It breaks my heart," Garcia says. "This is an everyday occurrence for a lot of people here in Mesa."

Mesa attorney and Hispanic activist Phil Austin says Pearce and his allies are using the oldest political trick in the book.

"He is the Joe McCarthy of his era," Austin says. "It’s a political ploy. . . . He’s playing on the fears of people, because they’re afraid of the change that’s going on. And he’ll ride those fears as far as they will take him."

Pearce refused to be interviewed for this story, but he’s made his views quite clear. Since leading the campaign for the antiillegal immigrant Proposition 200, he has become a nationally known immigration reformer. Earlier this month, he advised Colorado legislators interested in a similar ballot proposal. He says he supports legal immigration and wants those who come to the U.S. to abide by American customs.

"We need some policy reform where (when) you come here, you’re expected to be a loyal citizen of the United States of America and assimilate, not a clash of cultures," he said at a Brookings Institution forum in Washington, D.C., in December.

"You must come here with the right attitude. You must come here and be self-sufficient. If you’re going to come here, you’ve got to assimilate and be an American, and that means you’ve got to fit in and be patriotic."

MESA’S TRANSITION

Mesa is struggling with the same immigration issues as Phoenix, Glendale, Tempe and other Valley cities. But to people here, it feels different.

Perhaps it’s Mesa’s reputation as a bastion of Mormon conservativism. Or the fact that the city has a growing population of day laborers, who despite their immigration status are critical to the Valley’s economic development.

"I’m here to work. Solamente," says Domingo Fernandez as he stands in the shade of a block wall along Broadway near Gilbert Road with five other men, hoping to salvage a half-day of work. Earlier that morning, he says, there were at least 30 of them.

Fernandez, from Hidalgo, Mexico, says he walked for three days and nights to get to the U.S. about a year ago. He left behind a wife and two children, ages 3 and 10, to whom he sends money whenever he can.

Contractors hire him for landscaping and construction site cleanup. Sometimes, the men say, area residents hire them to do odd jobs around their homes.

Those on all sides of the immigration debate agree that enforcement is a key component of reform, and Pearce supports legislation to fine employers who hire illegal immigrants. Beyond that, though, there is broad disagreement about how to stem the flow of illegal immigrants and whether to provide some kind of documentation to those already here, such as a guest worker program.

And while there is some sentiment for allowing state and local law enforcement to help enforce federal immigration laws, determining who is here illegally and then deciding what to do with them is well beyond the scope of most cities, including Mesa.

"Congress has dropped the ball," says attorney Julie Pace, an employment-law expert who grew up in Mesa. "But they don’t want to take the heat for it, because it’s controversial and they really know that they need the workers or this country would stop."

Pace, who advises businesses on immigration law, says demographics show there are not enough American workers to fill jobs in the growing service-based economy, nor will there be in the future. The trick for employers is to find workers who are legal without violating laws against discrimination in the workplace.

"You may not presume that people aren’t here legally simply because they have brown skin or speak another language," she says. "We want people who can come in legally and pay their taxes and be treated with respect. Employers are stuck in a horrible Catch-22."

WHY MESA?

Julie Pace is vice chairwoman of the Arizona Chamber of Commerce immigration task force. She comes from a fourth-generation Mormon pioneer family, attended Fremont Junior High and was in the first graduating class at Mountain View High School. Latinos and Mesa’s once-dominant Mormons, she said, are remarkably similar.

"We have always had a large Hispanic community (in Mesa)," she said. "When you get down to the values of Mesa, they’re very family-oriented, they’re very church- oriented, very kidoriented. They have the same work ethic that the Mormon pioneers had."

Statistically speaking, however, the new arrivals are younger, poorer and less educated than the rest of Mesa.

They say they have settled in the city for the same reason Anglos do — it’s a great place to raise a family. The crime rate is low, the schools are good, housing is more affordable than in other parts of the Valley and the work is here.

At 24, the median age of the Hispanic population in Arizona is 10 years younger than Anglos — in the prime of child-bearing years. The Hispanic birth rate is higher than any other ethnic group in Arizona and in the U.S.

"It is a fact that the nonminority population is decreasing and aging rapidly," Olivas says. "On the opposite extreme, there is a very young, vibrant minority population led by Hispanics. Proof of that is the incredible transformation in Mesa’s public schools."

While Hispanic children typically are receiving a better education than their parents, and Hispanic students from Mesa have become student government leaders, valedictorians and Ivy Leaguers, Latino students as a whole still lag behind in the Mesa school district.

Minority students are more likely to come from poverty and arrive at school speaking Spanish as their first language. More than half of the children attending Mesa schools are poor, up from 30 percent in 1991. While nearly every family spoke English as their primary language in 1980, one-quarter now say they speak something else, primarily Spanish.

Arizona has one of the highest rates of limited-English proficient students in the country, according to a new Urban Institute study, which poses huge challenges for educators. Nearly half of the children in immigrant families live with a parent who has not graduated from high school, which means the parents are less able to help with homework and less likely to be in well-paid, fulltime jobs.

The drop-out rate for Hispanics is nearly twice that of Anglo students, and passing rates for Latinos on the high-stakes Arizona Instrument to Measure Standards test consistently fall well below their peers.

"Many children who are immigrants do very poorly in school. Their children make up that gap," says Jim Zaharis, former superintendent of the Mesa school district, who has lived in Mesa since he was 3.

"One of the challenging dilemmas for educators today is, while you’re working to help that second generation, you have a pipeline of first generation always coming in," he says. "You open the door the next Monday morning, or the next September, and there’s a whole new group. And that is unlike many other states."

Pearce has said up to $1 billion annually is spent to educate the children of illegal immigrants. Mesa school district officials say no such number exists, in large part because schools cannot ask students whether they or their parents are legal U.S. residents.

This creates a paradox for educators, but their primary mission is to educate children.

"If a child is sitting at your door . . . you want them to succeed," Zaharis says. "The school administrator is in a difficult place. There are two laws that seem to be conflicting. One is that they need to come here legally. The other is, you need to give them an education. You don’t put that on the child."

HEALTH CARE PROBLEMS

If schools are the place where Hispanic growth is the most obvious, hospital emergency rooms may run a close second. Like classrooms, hospitals do not turn away patients they suspect are in this country illegally, nor can they under the law. While it is a mounting financial problem for hospitals and taxpayers, it is an even greater health issue for the Hispanic population.

Lack of insurance, coupled with language and cultural differences, lead to preventive health and treatment problems for Latinos. They are more likely to let small problems become larger, more expensive ones.

The burgeoning Hispanic population in Mesa means the problem will only continue to worsen.

"In our city, we lack resources for the uninsured, we certainly lack resources for any preventive services, and we lack health care workers," says nurse and Mesa Community College instructor Bertha Sepulveda, who leads a federally funded program to train Latino nurses from other countries to meet U.S. qualifications.

"We’re in a double crunch for bilingual health care workers because of our changing demographics and the need to be culturally competent."

The uninsured and undocumented in Mesa have only one place to go for medical care besides the emergency room — East Valley Family Care.

The federally funded clinic serves mostly women and children, mostly the working poor and mostly Hispanics. It is the busiest of Clinica Adalente’s six clinics and, though it doubled in size earlier this year, struggles to find doctors and nurses.

Dr. Luis Irizarry sees a wide range of health issues, from chronic problems like heart disease and diabetes to things that are more difficult to diagnose.

"Sometimes all they want to do is talk to somebody," he says. "There’s a lot of depression, stress. They come in complaining of pain, but often there’s something else behind it."

If he knows his patients, it’s easier to spot the emotional ailments. That’s why Irizarry encourages his patients to stick with him, even if they have to wait a few weeks for an appointment, rather than shop around. He also urges them to come to him for treatment rather than relying on home remedies or drugs dispensed by friends and relatives.

"Many of them are afraid to get care because they’re afraid they’re going to be deported back to Mexico," he says. "They prefer to go to friends."

He understands the concern about illegal immigrants using medical services. His own mother needs medication and treatment, he says, and why should she be in line behind someone who is not legally allowed to be here?

"We can go on with the debate, but the bottom line with these patients is, we all need care," he says. "My job as a doctor is to take care of ill people, regardless of whether they are Mexican or Chinese or Martian."

Bertha Sepulveda raised two children in west Mesa while building a successful career as a public health nurse, educator and consultant. She came out of retirement to run the nursing program for native-born Hispanic nurses in the Maricopa Community College District. She believes that bilingual, bicultural health care professionals are critical to the health and well-being of the East Valley’s growing immigrant population, and will save taxpayers money in the long run.

"They come here because they are looking for a better life. They are looking for a way to feed their family," she says. "The first and only way is to understand this population. To understand why they’re here."

BUSINESS IS BOOMING

The business community certainly seems to understand. From billboards to Spanish-language media, businesses are tapping this gargantuan and growing market.

Hispanic buying power increased in Arizona from $8 billion to $21 billion over the last decade, according to the Datos 2005 study, released earlier this month by the Arizona Hispanic Chamber of Commerce.

In the Valley, Hispanic households control nearly $15 billion in spending, 55 percent of Hispanic households own their homes and 86 percent have at least one bank account. The average annual household income is $51,525.

"Based on the census numbers, if you’re not doing multicultural marketing . . . or having dollars allocated toward the Hispanic market, you’re just waiting to go out of business," says Greg Patterson, the son of a former Chandler mayor and owner of Andale Communications in Mesa.

According to the Chain Store Guide, Hispanics’ disposable income nationwide has jumped 29 percent since 2001 to $715 billion last year, double the pace of the rest of the U.S. population.

Hispanic buying power is growing at a rate of 118 percent and is expected to reach $1 trillion by 2008.

Advertisers have almost doubled their advertising efforts targeted to Hispanics.

Hispanic teenagers control 15 percent of the teen market and are expected to account for 60 percent of total U.S. teen growth from 2000 to 2020.

FITTING IN

While hanging onto their Latino roots and customs, Hispanics in their teens, 20s and 30s are pursing the American dream with a vengeance and are well on their way to forever altering the political, economic and cultural landscape in the East Valley.

By 2020, second-generation Latinos — U.S.-born children of immigrants — will outnumber new arrivals and third-generation Hispanics, according to Datos 2005, an annual Hispanic trend report compiled by Loui Olivas from U.S. Census data, the Pew Hispanic Center, the Urban Institute and other sources.

While there is no data available specifically for Mesa, there is no reason to think the booming Hispanic growth rate here will shape up any differently.

Record immigration and high fertility among immigrants will combine for some staggering statistics: Between 2000 and 2020, the number of second-generation Latinos in U.S. schools will double and the number in the U.S. work force will triple, according to a study by the Pew Hispanic Center.

"Regardless of whether immigration flows from Latin America increase, decrease or stay the same, a great change in the composition of the Hispanic population is under way," the study says. "The rise of the second generation is the result of births and immigration that have already taken place, and it is now an inexorable, undeniable demographic fact."

These young men and women are both Latino and American, and together with other secondgeneration minorities they are introducing new music, foods, language and attitudes while adapting to Anglo customs and laws that may have confounded their parents.

They will be better educated, substantially bilingual and, as a result, will earn more than the first generation, according to the Pew study.

They will open new stores and restaurants, buy their first homes and log on to the Internet in record numbers (one out of every two new Internet users is Hispanic). And as their education and incomes improve, so goes the baby boomers’ retirement.

"It’s exciting because of the richness in diversity, culture and customs that population brings to the community. It re-energizes development and it rekindles neighborhoods," Olivas says. "And eventually you have a minority work force supporting a predominantly non-Hispanic retired community.

"So be kind to your minorities, because in their future lies your Social Security check."

Despite their numbers, a sizeable percentage of Hispanics are ineligible to vote — either because of age or citizenship status, according to the Pew Hispanic Center, and among those who are eligible less than half go to the polls.

With time, Olivas says, the three things that make committed voters — age, education and income — will apply to more Hispanics, thus empowering the electorate to put more Latinos into office.

And with time, Anglos and Latinos will fuse into a stronger, albeit different, American culture.

"You can’t stop it," Olivas says. "The only thing I’m hoping people will do is embrace it, accept it and help these new communities become stronger communities."

- Tribune writers John Yantis, Kristina Davis, CeCe Todd, Blake Herzog and Brian Powell contributed to this report.

|

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703348 |

Fort Worth, TX Republican administration +2/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/13/2021 12:36:33 PM

Reply to: 2703325

|

|

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703350 |

Fresno, CA Republican administration +2/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/13/2021 12:39:34 PM

Reply to: 2703348

|

UPDATED AUGUST 15, 2020 11:04 AM

Five Fresno residents share their economic circumstances and experiences as members of the Black community. Here’s a glimpse into the stories of Windell Pascascio, Dr. Reshale Thomas, Bob Mitchell, Angie Barfield and Pastor DJ Criner. BY BRITTANY PETERSON | CRAIG KOHLRUSS | JOHN WALKER

When Booker T. Lewis, pastor of Rising Star Missionary Baptist Church in southwest Fresno, moved from Greenville, Texas, to Fresno in 1977, he was 16 years old and a sophomore in high school.

He remembers his first days at Edison High School and the sea of Black faces.

“I never saw so many Black people in one place,” he said. “Where are the white people?” He sought answers from the principal and was told that more than 98 percent of the school population was Black.

Even the schools in Greenville, Texas — a town that flaunted its residents’ intolerance of Blacks — were integrated. Lewis’ family lived in southwest Fresno in a solidly Black neighborhood; his father pastored a church that had an all-Black congregation. “Most of the Black lives in Fresno were spent west of Highway 99,” he said.

Brian Marshall, former director of transportation for the city of Fresno (2014-2017), said that the physical separation of the African American population in Fresno to “one little corner of the city” tells the “tale of two cities” eloquently.

In their “little corner” of the city, Fresno’s Black residents lag behind other races in economic participation. They are more likely to be unemployed and to live in poverty. Racial disparities in employment rates, wages, wealth, housing, income, and poverty persist. They also have fewer prospects for economic success because of myriad factors, including what Esmeralda Soria, a member of the Fresno City Council for District 1, calls a systemic “disinvestment in the (city’s) African American community.”

According to the U.S. Census, the median Black household earned just 59 cents for every dollar of income the median white household earned in 2018. During the same year in Fresno County, the median income for a Black family was $32,571 compared to $51,261 for a white family.

Nationally, the poverty rate for African Americans was 20.7% during the 2018 economic boom and 8.1% for whites. Twenty eight and half percent of Black children under age 18 lived below the poverty level in 2018, three times as likely as much as white children (8.9%). The poverty rate for Black residents in Fresno County was 30.6% in 2018.

Tania Pacheco-Werner, sociologist at Fresno State, said the disinvestment in areas heavily populated by Blacks results in severe burdens of poverty, making it difficult for residents to maintain positive outcomes in most spheres of life. In Fresno, as in many parts of the country, Blacks and whites live in different and unequal worlds. This inequality is not accidental, but rather a result of Fresno’s distinct culture as well as policy choices by elected officials.

“It is like it is two Fresnos in the same place,” said Pacheco-Werner. “Fresno was developed into north and south with the railroad in mind — providing the physical separation.”

Alan Autry, former mayor of Fresno (2001-2009), used the term “A Tale of Two Cities” to describe the disparity in income, property value, economic investments and quality of life between north (mostly white) and south Fresno (mainly populated by communities of color). The 1977 Edison plan by the Fresno City Council warned that the continued neglect of the southwest part of the city threatened to “transform racial segregation into economic segregation.”

Today, statistics show persistent racial disparity in employment rates, wages, wealth, housing, income, and poverty is par for the course in Fresno.

But the current situation — with African Americans facing major economic and physical catastrophes on two fronts: greater vulnerability to the COVID-19 virus — coupled with the relentless racial justice movement since the murder of George Floyd — has created an urgency and reignited the old conversations about who or what is responsible for the conditions of Fresno’s Black residents and what can be done to address the wrongs.

PANDEMIC BY THE NUMBERS

In Fresno, Blacks make up just 7.5 percent of the population, but account for 40 percent of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Additionally, the infection rate for Black residents is 100 per 100,000 cases, which is four times higher than the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) community spread prevention guidelines of 25 per 100,000 residents.

“Black folks in Fresno and across the nation are the most vulnerable across every health, social, economic and well-being spectrum measure,” said Shantay Davies-Balch, president and CEO of the Black Wellness and Prosperity Center, and a representative of the Fresno African-American COVID-19 Coalition. “Their comorbidity — the burden of heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, etc. — contribute to infection vulnerability and morbidity trends.”

The pandemic has also aggravated an already fragile economic situation. Black workers were economically insecure before the pandemic, and the rules instituted to contain the spread of COVID-19 magnified the economic damage to these workers and their families. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Black unemployment rate was 16.1% at the end of the second quarter of 2020, compared to 6.1% in 2019.

To underscore the gravity of the pandemic fallout among Fresno’s Black community, the African-American COVID-19 Coalition presented an investment plan proposal to the Fresno City Council on June 15, aiming to rectify the disproportionate impact the pandemic has on the group.

“It’s time to demand that city and county leaders invest in us after generations of discrimination, criminalization, disinvestment, and polluting our community,” Davies-Balch said in an interview.

UNEMPLOYMENT AND ECONOMIC MATTERS

“[In southwest Fresno] If I am on the wrong path and want to quit the street life, I can walk in any direction for half a block, I should find a church or place of worship,” Myrick Wilson, owner and CEO of Mad illustrators, a silk screening company in southwest Fresno, explained. “But if I want to get a job or a training, I have to get in a car or bus or Uber, and drive miles outside of my neighborhood to find a place to give me an opportunity to work or to get training.”

The “Unequal Neighborhoods” project, led by Pacheco-Werner, highlights the stagnation in the lives of Blacks.

Those in southwest Fresno, according to “Unequal Neighborhoods”, are “unable to meet the minimum basic income” while white neighborhoods are “at least three times more likely to meet minimum basic income than Southwest Fresno.”

INTENTIONAL NEGLECT — OR IGNORANCE?

Why the persistent suffering and poverty among Fresno’s Blacks? The answer is as complex as the causes and has its roots in the history of Fresno.

“It is about what the city has done in the past; the Black community has resided in southwest Fresno, which has not seen the kind of investments for economic developments that occurred in the northern part of the city,” Soria said. “We talk about the Tale of Two Cities. I recognize that that (investment) hasn’t been good enough.”

According to Myrick Wilson, west Fresno suffers from a lack of places for career or vocational preparation. “Nothing is here in west Fresno,” he said. “We are in a deficit. The numbers and statistics show we have a lot of needs to fill.”

![Tara Lynn Gray.jpg Tara Lynn Gray.jpg]() Tara Lynn Gray, President & CEO of the Fresno Metro Black Chamber of Commerce & Chamber Foundation, photographed in Fresno on Thursday, Aug. 14, 2020. CRAIG KOHLRUSS CKOHLRUSS@FRESNOBEE.COMTara Lynn Gray, CEO of the Fresno Metro African American Chamber of Commerce, said that even when unemployment is at its lowest and the country is approaching full employment, Blacks still have double digit unemployment, “because of racism and because of disinvestment in our communities.”

Gray said, “There is not even a neighborhood store for a black man to get a job stocking shelves.”

A CEILING — GLASS OR BLACK?

“California is the fifth or sixth largest economy in the world, we are in the heart of this vast economy,” Wilson said. “Our numbers (economic) are worse than in some countries with troubled history, and to be one of the worst economic places in the world in America? That should not be.”

Why are Fresno’s Black residents not making greater strides toward equality in their workplaces?

Because, although Fresno is a large city, Lewis said, it still operates “very hometown-like” and “people will hire their relatives and only people who look like them” and that sets “a ceiling.” Blacks are not accepted or valued and that feeling of alienation lasts a long time, he said.

Upon graduation from Edison High School in 1980, Lewis enrolled at California State University, Fresno and started working as a janitor at GESCO, part of Guaranteed Trust Savings and Loan. A few years later, he was offered a job in the mail room and then promoted to operations. He started learning about programming and got a job in the field. He was one of a handful of Blacks in the company. He kept getting promoted until 1987.

“I hit a ceiling,” he said.

Lewis found out after he applied for a managerial position but was turned down. He kept applying for supervisory positions, but kept getting rejections. He said he couldn’t understand why because all his reviews were stellar and he had been promoted in the past. What changed?

A white co-worker invited him for a talk outside.

“You will never get a supervisor’s position here,” he said the white man told him. “You are qualified, but they will never make you a supervisor or manager.” Because he is Black. That was the only explanation he needed.

Lewis left Fresno and moved to the Bay Area where he worked in technology, first as a lead operator, then a manager and finally a vice president, supervising many, including “six white men who had Ph.Ds.”

“My experience in the Bay Area is different from Fresno,” he said. “I never would have done that well here (Fresno) because there is just something about Fresno.”

More than three decades later, same problems, same theme, minor variations. Ella Washington just retired from the Internal Revenue Service in Fresno after 35 years. She held several positions in the organization, mostly in customer service and had a stint as a manager. She said the management at the IRS has different standards for evaluating Black and white employees. “We [Blacks] had to walk a straight line,” she said. “They picked on Black employees all the time.”

Washington recalls being reprimanded by the manager because she didn’t want to participate in picture day. Meanwhile her white colleagues who were caught drug dealing were not punished.

When Washington held an interim manager’s position and had to keep attendance, including all tardiness, she realized after several discussions with the management that white employees’ excuses for lateness were always valid, but not so for African Americans. A Black manager who was out with a serious illness was hounded into taking an early retirement.

“I got tired of dealing with their stuff” and retired as soon as she was eligible, she said.

Even Black people with high levels of education and in high paying positions were not immune to workplace racism.

Another Black man, who did not want his name used for fear it would affect his present employment, was recruited three years ago to head a department within the city of Fresno, but left one year later.

“I knew within the first month that I made the wrong decision coming here,” he said, remembering feeling out of place and constantly under scrutiny. “I felt so uncomfortable; people wanted to target me.”

Without any support, he struggled and suffered migraines every night. “Racism played a part in everything here [Fresno].” He says it is extremely hard to describe what it felt like to work and live in Fresno, but he is happy to now be in a city where he knows he is valued.

GOT HOPE?

“The Fresno City government must create policies to uplift the Black communities which have been decimated by poverty,” Soria said. “We, as a city, have a responsibility to figure out how to fulfill our responsibility to uplift every one, especially now when the issue has become national.”

JOB TRAINING WITH A PURPOSE

Former Fresno City Council member Oliver Baines, chair of the Fresno Police Reform Commission and president of the Central Valley New Market Tax Credit Fund, said job training is the path to ending poverty and the desolation in southwest Fresno.

![JRW MLK MARCH 9 JRW MLK MARCH 9]() Then-Fresno City Councilmember Oliver Baines delivers a forceful speech during a Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day rally at City Hall, Monday morning, Jan. 15, 2018. JOHN WALKER JWALKER@FRESNOBEE.COMIn the past, job training wasn’t planned with the people that needed it in mind. The centers were often located outside of the area where the needs were, and the programs would create insurmountable road blocks, like requiring that enrollment be tied to a clean background check. “You heavily criminalize the area, and because of racial profiling, people enter the system,” Pacheco-Werner said. “So they create all this ecosystem for Blacks that sets them up to fail.”

“That is why I started mine,” Baines said. “It was frustrating to see young men and women get screened out before they get in. I make a point to not screen people out. I make a point to screen people in.”

Baines said also that most of the other programs did not have a favorable outcome and “people were not being hired” after completing job training programs.

“Going through a job training program should be the same as going to college — to be more attractive to employers and get meaningful employment — the kind that keeps them off social programs,” he said.

So the intense 12-week job training that Baines operates in partnership with the Fresno Economic Opportunities Commission is different. The Valley Apprenticeship Connections is located in downtown Fresno and tied to jobs. In fact, his trainees are often employed before they complete the training program.

“All I want is for students in my program to be able to have a lifestyle similar to mine,” he said. “My goal is a workplace where they can escalate and move into the middle class.”

He said he started by talking to employers to find out what skills they wanted in an employee and then got guarantees that a “young man or woman who possesses the required skill sets would be hired.”

Employers said the hardest thing for them was finding employees with basic social skills — listening, taking directions, punctuality and dressing appropriately. So the Valley Apprenticeship Connections program devotes a lot of time to soft skills while giving trainees a blend of everything the employer wants, including hands-on experience in the construction field. More than 80 percent of the graduates are employed immediately at an average starting wage of $20 or $21 an hour over minimum wage, Baines said.

“I want everyone the way they are,” Baines said, so the program “purposely recruits parolees, probationers, people on welfare,” and those who would never get into traditional job training. “So many of my students come with previous addictions and drug use records and gang backgrounds. I intentionally look for parolees and probationers.”

Job training has to be about getting a job, Baines said, adding that to change the employment situation for Blacks, everyone needs to acknowledge that there is racism in employment. “Racism is systemic — we need to understand that the system in many ways is set up with racism embedded in them.”

Baines said his program changes people’s lives everyday.

“Nothing is impossible,” he remembers the story of a former trainee who was imprisoned for 19 years. Now the man earns more than $40 an hour. Baines said the training program is “The best work I have ever done or will ever do.”

Dympna Ugwu-Oju is the editor of the Fresnoland Lab at The Fresno Bee, a team of journalists focused on reporting stories at the intersection of housing, water, neighborhoods, and inequality.

RELATED STORIES FROM FRESNO BEE

AUGUST 03, 2020 11:49 AM

JULY 24, 2020 10:42 AM

JULY 13, 2020 2:25 PM

JULY 28, 2020 5:00 AM

READ NEXT

Fresno’s “anti-Black sentiment” must be “broken” if the community is serious about solving these problems, one teacher said.

KEEP READING

TRENDING STORIES

SEPTEMBER 12, 2021 5:00 AM

UPDATED SEPTEMBER 11, 2021 10:40 PM

UPDATED SEPTEMBER 12, 2021 04:42 PM

UPDATED SEPTEMBER 12, 2021 04:47 PM

UPDATED SEPTEMBER 12, 2021 04:27 PM

UPDATED SEPTEMBER 10, 2020 10:55 PM

UPDATED SEPTEMBER 11, 2020 01:46 AM

UPDATED SEPTEMBER 10, 2020 11:00 PM

UPDATED AUGUST 18, 2020 12:18 PM

UPDATED AUGUST 16, 2020 08:56 AM

COPYRIGHTPRIVACY POLICYTERMS OF SERVICE

|

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703445 |

Fix it. +0/-2

|

Author:Shooting Shark

9/13/2021 8:25:13 PM

Reply to: 2703320

|

Put you money where your mouth is Crowbot . Buy a slum. Good luck collecting rent. Just call it rresridtribution of YOUR wealth.

Theres a reason the poor are POOR.

Hint it ain't "racism"

Useful idiot! |

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703562 |

"Put you money where your mouth is Crowbot . Buy a slum. Good luck collect" +1/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/14/2021 3:17:26 PM

Reply to: 2703445

|

"Put you money where your mouth is Crowbot . Buy a slum. Good luck collecting rent. Just call it rresridtribution of YOUR wealth."

Intentionally obtuse, I hope. There is really good money in slum ownership. And prostitution, drugs, human enslavement. I don't have the personality or training to make money in those fields.

There are also reasons why it seems that poverty is concentrated in urban areas. It seems so because people of all kinds, black white, red, brown, whatever, are concentrated in urban areas. That's where economic status is most visible.

It isn't so:

Yes, there are reasons why poverty exists in America. It is not simple racism, although racism has an effect on economic status. That's why the average black American family only has one-tenth the wealth of the average white American family. Explain that without racism.

|

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703565 |

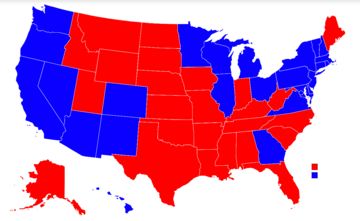

Put that map in perspective, red states and blue states +1/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/14/2021 3:22:35 PM

Reply to: 2703562

|

Aside friom the newer, Western states and Georgia, poverty and political affiliation go hand in hand- |

|

Return-To-Index

|

|

Msg ID:

2703323 |

Report highlights racial disparities among Jacksonville’s children in pover +3/-0

|

Author:TheCrow

9/13/2021 11:38:17 AM

Reply to: 2703313

|

Jacksonville, FL, for instance? I can cite some more big Republican run cities with racial disparities if you like. Your position is laughable, typical Trumpist ignorant prejudice.

The Jacksonville City Council is the city's primary legislative body. It is responsible for adopting the city budget, approving mayoral appointees, levying taxes, and making or amending city laws, policies and ordinances.[5]

Membership

- See also: List of current city council officials of the top 100 cities in the United States

The Jacksonville City Council is made up of nineteen members. Fourteen are elected by district, while five are elected at large.[6]

A current list of council members can be found here.

Council Committees

The Jacksonville City Council features five standing committees and two special committees that focus on individual policy and legislative issues. Generally, the drafting of city legislation begins with the committees.[7]

A current list of Jacksonville City Council committees can be found here.

Boards and commissions

A series of advisory boards and commissions that are made up of non-elected citizens, whom city council members have appointed and approved, advises the Jacksonville City Council. The roles of these boards and commissions are to review, debate, and comment upon city policies and legislation and to make recommendations to the city council.[8]

For a full list of Jacksonville city boards and commissions, see here.

Other elected officials

Duval County residents also elect the following public officials:

|

|

Duval County Clerk of Courts

|

Jody Phillips

|

January 5, 2021

|

Republican Party

|

|